What Is Adjustment Disorder? Signs, Treatment Options

Often when people start feeling anxious or sad more often than they should, we assume they might be struggling with anxiety or depression. Yet, there’s another mental health disorder that presents with symptoms of anxiety, depression, or sometimes both. Adjustment disorders can look very similar to these other common mental health conditions, but with one important caveat: They’re triggered by a stressful life event.

Though most commonly diagnosed in children, according to the Johns Hopkins Psychiatry Guide, adjustment disorders are becoming more prevalent in adults as we all continue to struggle to adjust with the circumstances COVID-19 has thrown at us.

Here’s what you need to know about adjustment disorders, how to spot the signs in yourself and others, and how to treat it.

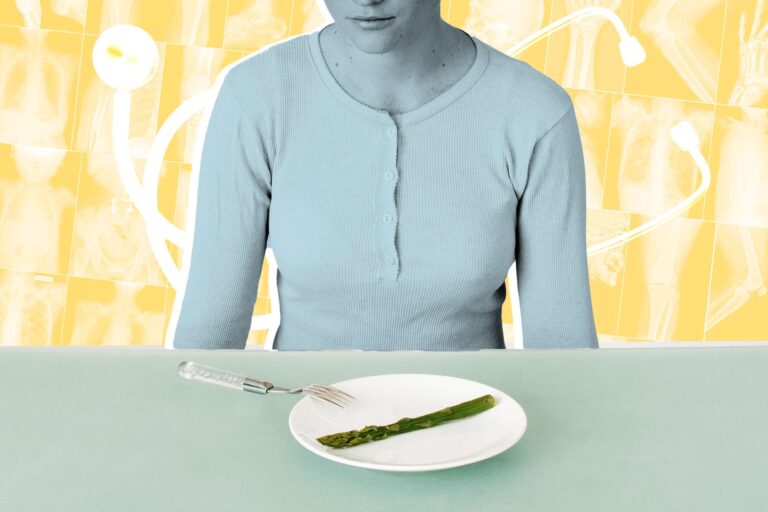

Adjustment disorders are largely related to high-stress events. When something extremely stressful happens — a divorce, loss of a job, the death of a loved one, an accident that causes you to lose your house or to be seriously injured, or any number of other things — people sometimes cannot bounce back. They might feel symptoms of depression, anxiety, or both. They might start acting out behaviorally or be unable to eat or concentrate on work or life.

“It’s a reaction to a stressful life event that is causing significant disturbance in your life,” Lindsay Henderson, PsyD, a therapist with Amwell, tells Health. While it’s normal to feel sad, restless, or overwhelmed after a big stressor, when suffering from an adjustment disorder those feelings rise to a point that is disproportionate to the stressor itself or last longer than they normally would, Dr. Henderson says.

Often, adjustment disorders look similar to depression or anxiety. “When we look at diagnosing adjustment disorders, we can categorize and say, ‘This is an adjustment disorder with depressed mood,’ or ‘This is an adjustment disorder with anxiety,” or it can be a mix of both depression and anxiety,” Dr. Henderson says.

Yet, “adjustment disorder” is not a term most patients use when they first seek help. Most of the time, people coming into Dr. Henderson’s office will say, “I just can’t seem to get over losing my job,” or “I can’t seem to manage everything in my life the way I used to.”

Commonly, adjustment disorders also show symptoms like trouble concentrating or trouble with memory. Gina Shuster, LMSW, a therapist at Oakland Psychological Clinic, sees patients who say “I’m so forgetful now and I never used to be this way;” “I get so flustered all the time;” or “I can’t find the right words.” With anxiety disorders that present as anxiety or depression, Shuster says, your body is spending so much energy just trying to maintain itself at this heightened emotional state that little things like memory and concentration start to slip. “It’s like juggling a bunch of different balls in the air. Eventually, some things are going to have to be let go,” she says.

It will come as no surprise to those of us who have lived through the last several months that COVID-19 has been one big stressor. According to Johns Hopkins Psychiatry Guide, triggers for adjustment disorders can be stressors that affect whole communities. And many people have been dealing with additional stressors on top of worrying about the virus: many have lost work, lost loved ones, and been forced to miss out on milestones like high school or college graduation, starting kindergarten, and throwing their weddings.

All of these stressors add up to a surge in people seeking therapy to find a way to cope, as well as greater reports of mental health struggles than ever before.

A CDC report published August 14 and examining mental health in the U.S. during one week in June, 2020, found that 40% of adults reported struggling with mental health or substance abuse. More than 25% of the 5,412 people who took the survey reported anxiety symptoms, up from 8% prior to the pandemic, and the prevalence of depression was four times greater than pre-pandemic (24.3% up from 6.5%).

Many of those who now feel anxious or depressed are likely suffering from an adjustment disorder triggered by coronavirus. “I’ve seen more people who are coming in saying that their usual coping skills just aren’t working anymore. They’re feeling overwhelmed and having a hard time managing their lives,” Dr. Henderson says.

Shuster has seen an incredible increase in new patients, as well. “We’re seeing a lot more adjustment disorders because everything is uncertain right now,” she says. “And people are experiencing major losses or have had to cancel things that they’ve been looking forward to for a year or have been unable to celebrate accomplishments that they were so excited and so proud of.”

When talking to these patients, Dr. Henderson’s first step is to try to put their struggles into perspective of the immense stress we’ve all been under both as individuals and as a society. “When you’re living in it, it can sometimes be hard to recognize, appreciate, or really understand just how depleting a global pandemic can be on your internal resources,” she says.

Adjustment disorders that present as depression, anxiety, or both are treated similarly to those disorders, with the exception that therapy is often focused on the stressor that triggered the adjustment disorder.

“We want to be able to identify triggers, but also be able to identify ways to calm down,” Shuster says. She offers her patients grounding techniques, which are similar to mindfulness practices and are meant to help people who might be close to a panic attack or be lost in depressive thoughts to focus on where they are in the moment.

One popular grounding technique Shuster likes is called “5-4-3-2-1.” It draws on all five senses, and it works like this: When you start to feel overwhelmed, stop wherever you are and look around. Name five things you can see. Then, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and, if possible, one thing you can taste.

Coping skills like this exercise help bring people who feel overwhelmed back to the moment. Dr. Henderson also works with patients on cognitive behavioral therapy, which aims to change the way we think and offer coping mechanisms for when our thoughts start to spiral. Often she sees patients who engage in two main forms of negative thinking: catastrophizing and black-and-white thinking.

“Catastrophizing is assuming that the worst is going to happen. So, ‘We’re in economic instability, I’m definitely going to lose my job. I’m not going to be able recover, and we’re going to lose our house,” she says. “While black-and-white thinking is seeing things as all good or all bad, and not allowing for a middle ground.”

Dr. Henderson works with people who have adjustment disorders to examine their thoughts and behaviors and make small changes in their thinking patterns, which can lead to better mood overall.

It’s of course also important to be proactive, rather than simply responding to triggers or already heightened emotions. “The first step in exploring mental health and emotional well-being is making sure that someone is doing the bare minimum to take care of their body and their mind. Eating well and sleeping well. I mean, all the stuff we hear over and over again. But people do need reminding of how important these things are,” Dr. Henderson says.

Right now, in times when everyone is struggling emotionally, Schuster suggests starting a feelings journal to track your mental health. Then, you can look back and see that you’re actually coping much better now than you were a few months ago, and things really are getting better.

Another simple way to boost your own happiness is to do something kind for others. “I’m doing gratitude work,” Shuster says. And research shows that people are happier when they’re helping others. So bake a pie and drop it off to your neighbors, or go grocery shopping for your grandparents, or make a donation to an organization that’s keeping people safe. A little charitable work goes a long way in lifting your mood.